Seeds of Revolt

In the far far north, amongst the frigid cliffs of an arctic archipelago, below an icy crust of permafrost, are buried thousands upon thousands of seeds. Here, on the frozen Norweigan island of Spitsbergen, lies the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, one of the largest seed repositories in the world. The creation of a consortium of governments and international scientific bodies, Svalbard is our world’s biogenetic backup: if climate crises and rising geopolitical unrest destroy much of the planet, at least the globe’s plant species will be safe, secluded in the natural refrigeration of this northerly library.

While not all seed banks are quite as grandiose as Svalbard, the scale of its backers—governments and international bodies—is typical. The prob- lems seed banks address (loss of planetary crop diversity, the obligation to preserve a nation’s genetic heritage, the need for raw plant material for use in the elaborate experiments of mega agrobusinesses ) are of a large scale, so large that they can only be addressed through the cooperation of great political and technological might.

The necessarily grand scale of seed banks made the Yale School of Architecture’s first studio prompt—the design of a seed vault for an individual—a curious one. What megalomaniacal individual would take on the enormous challenge of a seed vault on her lonesome? This individual, I decided would have to be opposed to the standard power-bearers that otherwise bring seed vaults into being. She would be a slightly deranged, off-the-grid, revolutionary type, distrustful of political and technoscientific institutions. Such a person would see current civilization, and in particular advanced agriculture, as being beyond rescue; the only way to halt the destruction of the earth by genetically engineered farm products, according to this world view, would be through violent revolution. This person’s seed vault would be a kind of Noah’s arc, storing the pure seeds by which one can remake the world in the wake of its revolutionary destruction.

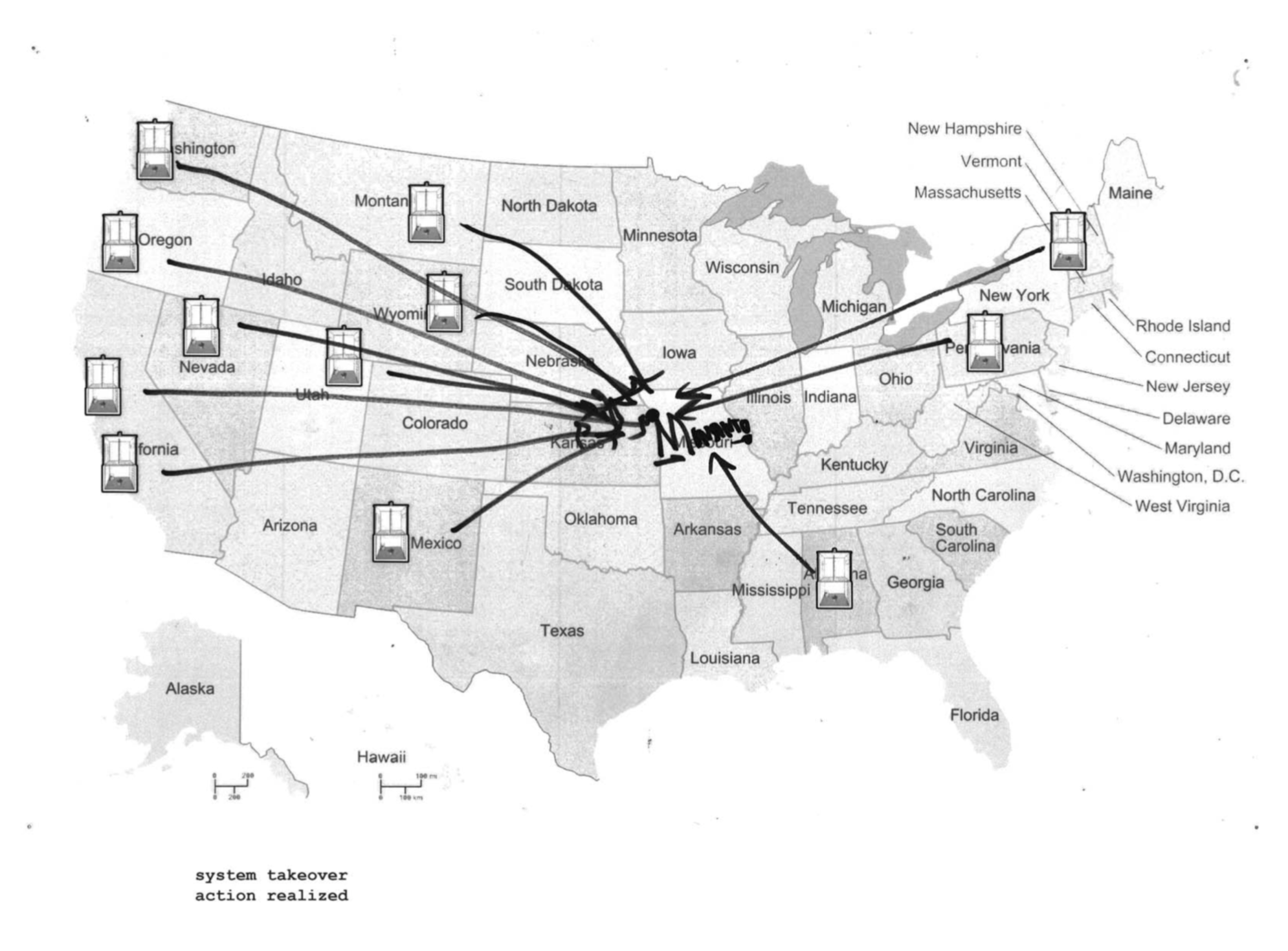

Inhabiting this mentality, I produced a zine that contained the radical writings and plans/instructions for a structure that would allow one to carry out this individual’s revolutionary aims. The structure is a simple shack: on the ground floor is a shelf for storing heirloom seeds and planting imple- ments, while on the hidden below-grade floor, there is a space for con- structing home-made bombs from fertilizer. Ideally the zine would recruit like-minded individuals to its cause, resulting in a network of these shacks across the country. When activated, this network of radicals would produce bombs en masse and launch a coordinated attack on Monsanto, the global head of genetically-altered seed production. Following this destruction, the network would then release their heirloom seeds, resulting in a brand new, ecologically pure world order.

Critic: Trattie Davies

< >