.

Shooting on Location

Starting in 1945, the LA-based magazine Arts and Architecture sponsored the design and construction of a group of forward-looking housing projects known collectively as the Case Study Houses. These were no mere exercises in design for design’s sake. At the moment of the program’s inception, the US was suffering a veritable housing crisis: thousands of GIs were returning home from their war service abroad but commensurate housing stock had yet to built. The magazine’s editor, John Estenza, a staunch promoter of modernist culture and values, believed that by giving carte-blanche to the finest minds in architecture, novel solutions to this pressing question of shelter would be found.In large measure, this utopian project has not aged well. While certain architects took this opportunity to attempt a radical reinvention of US housing stock—from proposing new spatial arrangements to advocating for industrial construction materials—given the advertisement-rich spreads they received in Arts and Architecture, along with the wealth of their clientele, the Case Study Houses are today associated less with their social ambitions and more with a certain 50s-era aesthetic of consumerist ennui. No Case Study House, however, suffered as dramatic a fall in grace as Case Study House 17. Designed by the architect Craig Elwood, the house began its descent almost immediately after its inception: the sprawling home—a single-story U-shaped arrangement of rooms nested around a shared courtyard and its obligatory pool—was designed for a large family, but these intended inhabitants found Elwood’s modernist deployment of glass and steel so off-putting that they sold the property within a year. The new buyers were the nouveaux-rich personified: Joe Swanson, a ris- ing screenwriter fresh off a great success at Paramount, and his aspiring actress wife Nora.

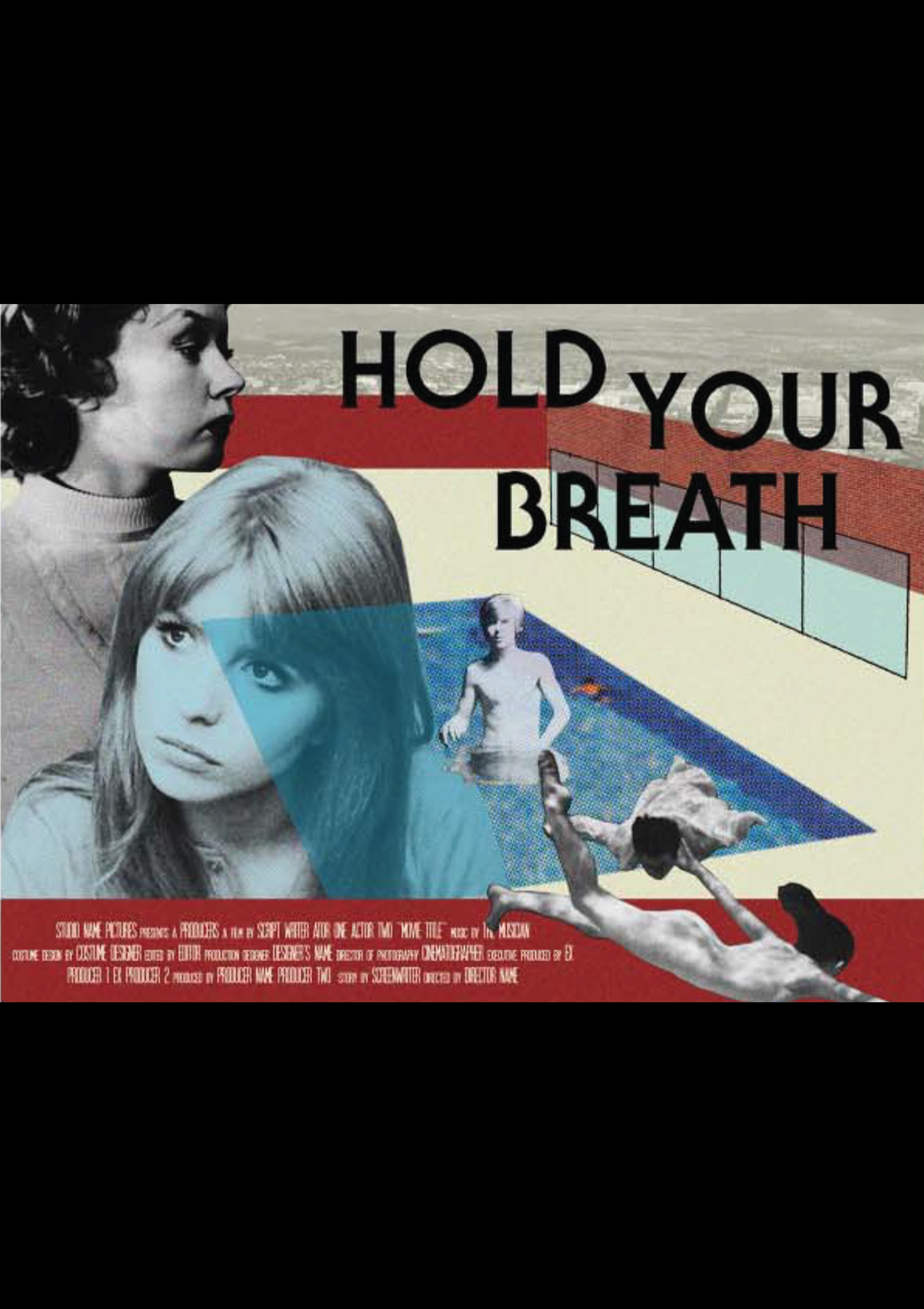

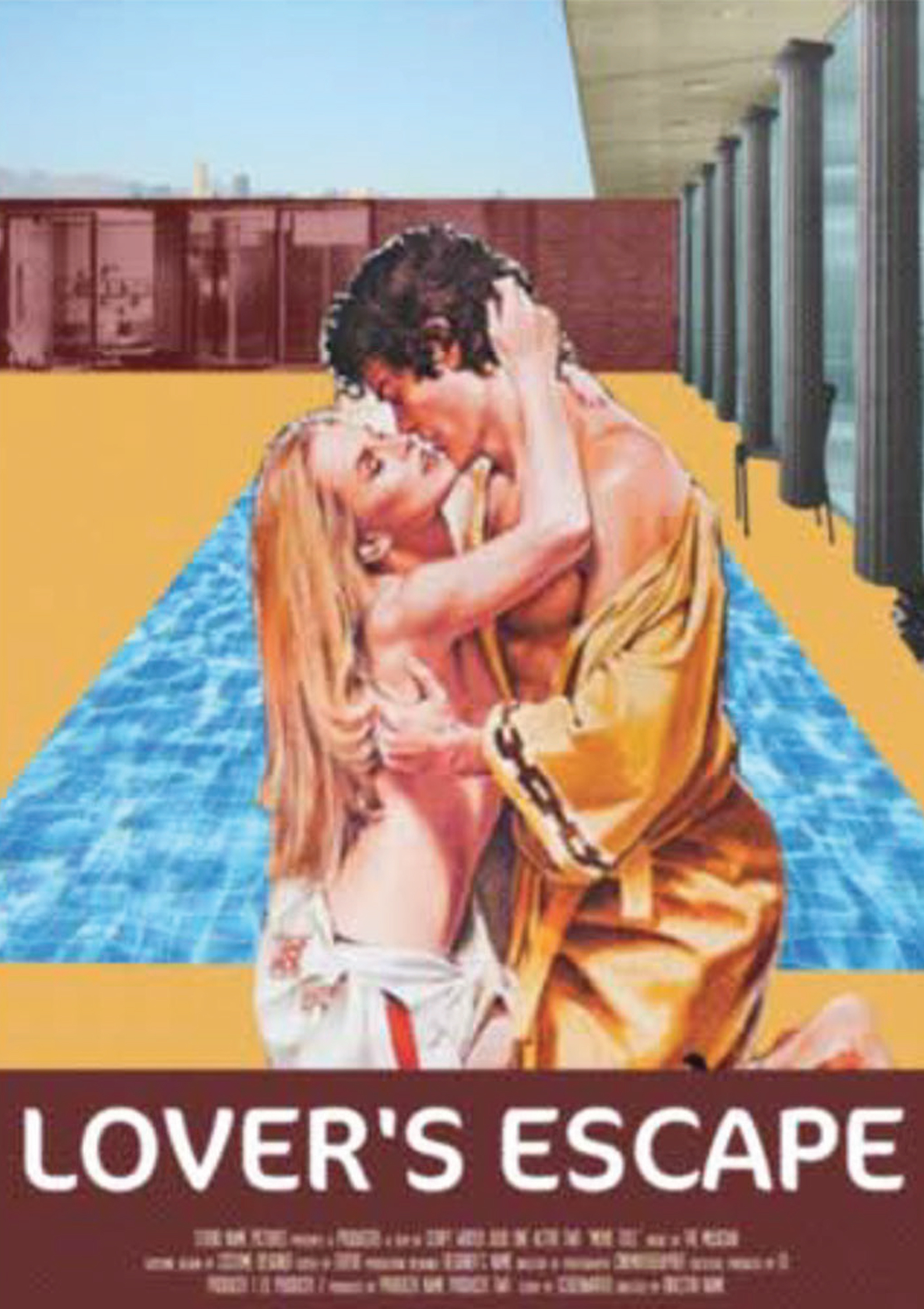

Shortly after buying the house, the husband’s creative energies ran dry and along with them his income. To make ends meet, the couple began renting the property out for film shoots. As they became increasingly financially desperate the productions grew seedier and seedier. Soon their domestic life was commingled with these bottom-of-the-genre-barrel stagings: their pool become host to soap opera marital fights, softcore pornographic theatrics, and countless B-grade action movie shoot em’ ups. The cycling shoots imposed increasingly déclassé alterations to home until Elwood’s high modernist, materially-reductive aesthetic had been papered over with ornate wallpaper and Plaster of Paris columns.

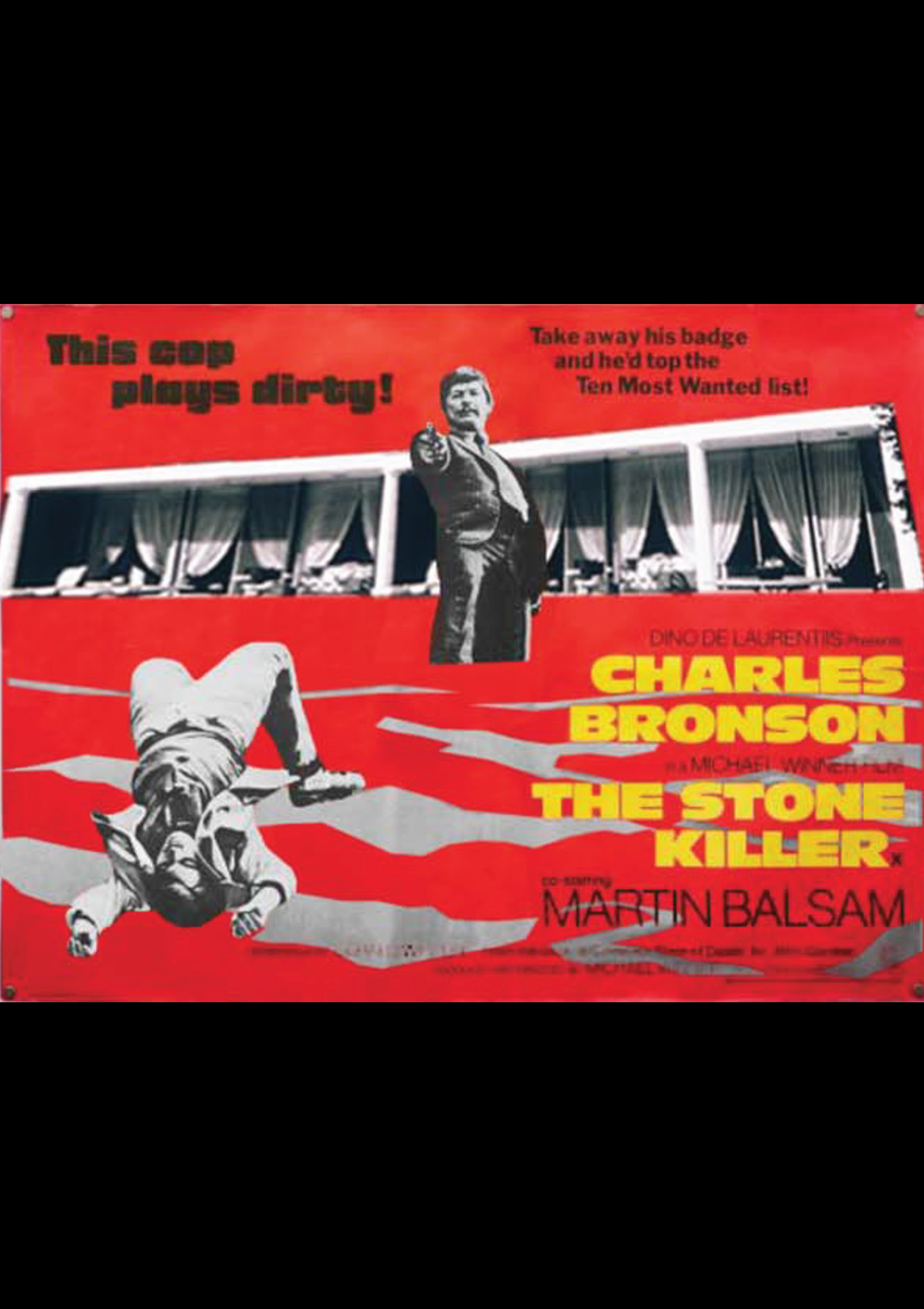

This architectural degradation was matched by a psychological one. Smiting from some minor spousal disagreement, one day Nora shot her husband dead. He fell face-forward into the pool where his body streamed out a ribbon of red that no filter could ever clean. Apparently, the commingling of fantasy and reality had proven too much for Nora: whether knowingly or not, this murder was an almost spot-for-spot remake of the fictional murder that occurred in the 1978 film The Stone Killer, shot on location at Case Study House 17. Modernist purity had never been so badly stained.

The Case Study House 17 Media Archive gathers all documentation of this architectural descent—from location release documents to movie posters to a New Yorker profile of the home. The posters are particularly revealing of the house’s debasement: high-budget productions feature a minimalist poster aesthetic more in keeping with Elwood’s original design, while the later posters’ gaudy graphics dovetail with the crass redesigns.

The above, unfortunately, is largely untrue. While Case Study House 17 was sold quickly by its original inhabitants and subsequently re-decorated in Hollywood Regency style, it never became home to countless film shoots and a ripped-from-celluloid true crime tale.