.

Perspecta 55: Futures Index

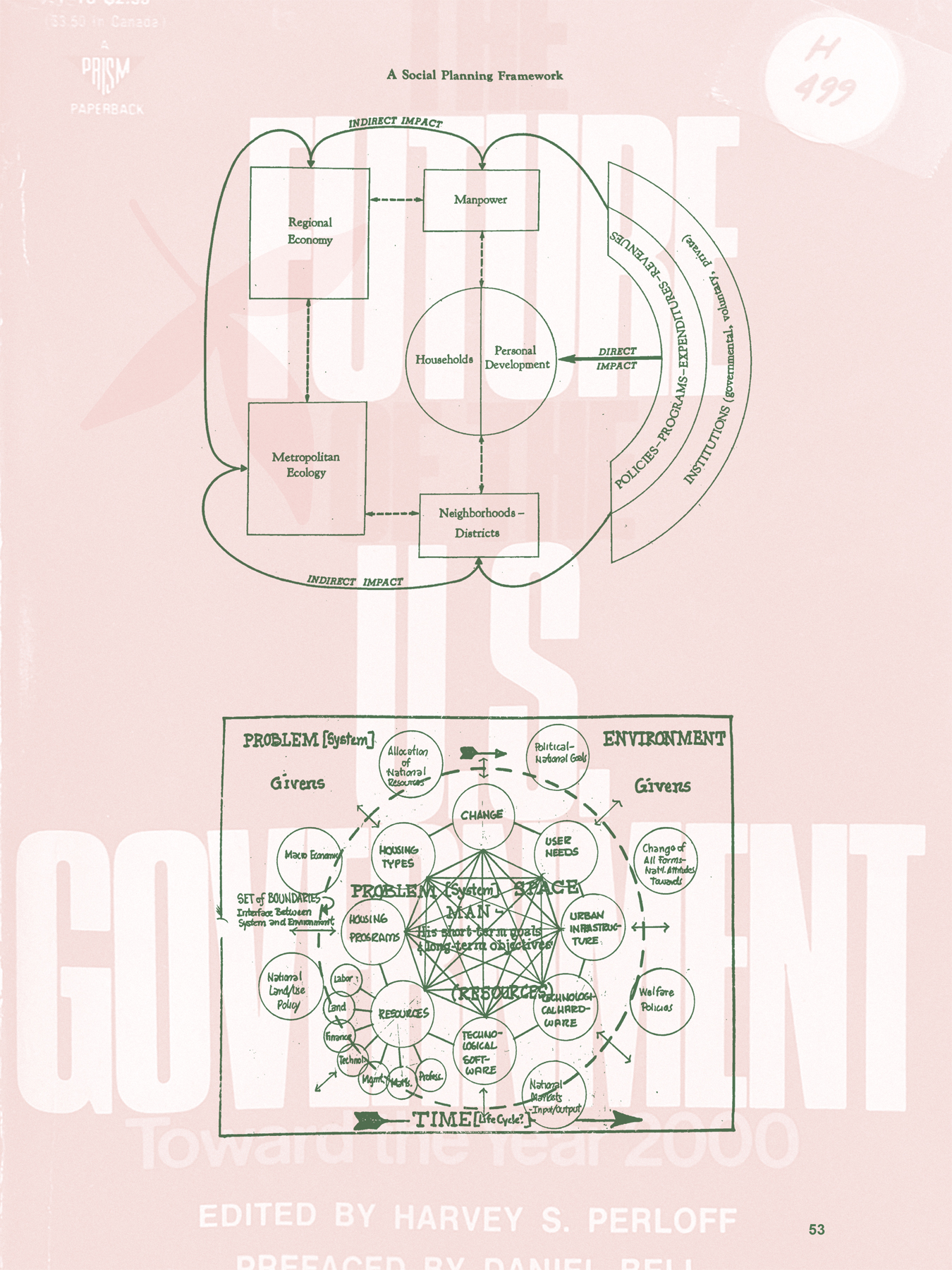

Increasingly, contemporary architecture practice has become dictated by projections of the future: our truss systems are modified to account for worst-case-scenario wind loads, we raise our machine room floor heights in accordance with 100-year flood projections and we choose our mate- rials according to long-term carbon footprint prognoses. If utopian archi- tects of the past sought to impose a future through visionary form, today the relationship has been reversed: first, a future is anticipated, then the architect designs her building in its image. The problem is, depending on who you talk to, the future is a radically different place.The algorithmically-inclined believe that through our ever-expanding store-house of information we are re-entering an era of divination. Like actuarialists on steroids, these big data evangelists deem themselves capable of highly accurate predictions. We only need to accrue enough data—more sensors on our buildings, more plug-ins for our digital models, more predictive simulations—and the future of our built environment will be optimized like never before.

Others see great uncertainty in the future. A number of theorists argue that our current state of techno-industrial development has produced a set of potential catastrophes—from nuclear fallout to human-induced climate change—without historical parallel, and thus without an archive of past events from which to make reliable predictions. Our only hope in the face of these unknown future disasters is to be prepared for everything: our walls must be able to withstand category 5 hurricanes, our cities have to be planned with an eye towards a nuclear attack, and our data storage centers need emergency backups.

Meanwhile, as omniscience and uncertainty face off, other disciplines get in on the futures action: business strategists roll out Herman Kahn’s scenario planning method, and financial specialists create ever more arcane tools of speculation, creating a market in a financial instrument literally called futures. Clearly, the future is contested territory. Architects, however, are content to be oblivious to these wars of anticipation. We blindly design our buildings in relationship to whichever prognosis has been handed to us at the moment: we take the disaster planner’s advice, we kowtow to the Revit plug-in, and we parrot rhetorics of resilience unthinkingly.

What we lose sight of in our subservience to these various futures is the fact that every form of prediction has its own social and political history, and thus its own highly specific set of values. Moreover, in our lack of curiosity, predictive methods with a range of validity are given a level playing field: complex climate models, which are the result of painstaking, decades-long work by the global scientific community are presented alongside more performative architectural diagrams that merely mimic the representational styles of scientific research.

Perspecta 55: Futures Index performs a much-needed analysis of these contrasting techniques of futurity, to discover their biases and the way they shape architectural practice. Specifically, we have identified five futurological practices as having a direct impact on our discipline—resource management, systems science, security planning, investment advising, and computation—and have asked a number of thinkers to provide critical commentaries on these forms of future-making and their impacts on the built environment. Without an analysis of these techniques of forecasting and the values they contain, we are doomed to cater our projects to imagined futures whose worldviews may not be our own.

A collaboration with Lani Barry, Jeffrey Liu, Nicholas Miller and Ethan Zisson.